In this exhibition of new work by one of New Zealand’s most scrutinised artists, Shane Cotton carries us with him on a continuing journey of discovery, uncovering the history of cultural exchanges between Maori and Pakeha. In examining the past, Cotton also presents us with the possible futures that face the people of New Zealand today. “Indeed, he has a great talent for enabling one to see, hear and feel very distinct and collective developments of a people, a place and a time.” (Ngahiraka Mason in Charles Green (Ed.), 2006 Contemporary Commonwealth, National Gallery of Victoria, 2006, p.56.)

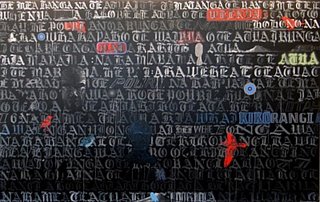

Throughout his career Cotton has developed an ongoing set of symbols and icons with which to present his stories for them to be read and deciphered. Two recent developments have been the reoccurring depiction of Hongi Hika, and a dense backdrop of calligraphic text. Birds also continue to populate Cotton’s works, symbolising the strong belief by Maori of birds as a spiritual guides and messengers.

Hika first appeared in a series of paintings Cotton developed for an exhibition in Australia. By following in the steps of Hika’s original voyage to Australia in 1814, Cotton felt it timely to include Hika as an important historic reference in his work. While in Australia, at the request of Samuel Marsden, Hika replicated his portrait, including his moko, by carving it on a fence post. Now held in the collection of the Auckland Museum, Cotton works from photographs of this historic relic, transporting Hika’s image into new “heavenly” realms. “Cotton’s painting immerses Hika in an ocean of deep black; the colour of harmony where all colours merge and become one. He paints Hika bathing in stunning hues of blue.” (ibid., p.59.)

It is easy to relate this image of Hika to that of the Maori shrunken heads that frequent Cotton’s paintings. The subject of Maori shrunken heads is a loaded topic. During the early European settlement of New Zealand in the 1800’s demand for these objects was strong, and they became scattered far and wide throughout Europe. Today, as some of these and other important objects are repatriated, the debate continues as to how they should be treated. Due to this, many of them are taken into museum storage, never to be viewed or displayed to the public. In turn, Cotton views his illustrations of such objects as a chance to breathe new life and vitality into these ancestors.

Text has always been intrinsic to Cotton’s densely narrative paintings. The script in these new paintings emulates the original handwritten copy of the English alphabet made by Hika while on his voyage from New Zealand to Australia. By referencing Hika’s trans-Tasman travels, at a time when Cotton himself is undertaking his own trans-Tasman explorations, Cotton endeavours to put himself in Hika’s shoes, making reference to issues of cultural displacement and the treatment of foreign cultures as novelties.

As always, these recent works from Cotton are highly thought provoking and informative. As Cotton states, “I’m not really trying to teach people, I’m trying to tell them what I’ve found.” (Shane Cotton quoted in Jim and Mary Barr, “Mana from Heaven”, World Art , no. 15, 1997, p.63.)

Visit

the site.

A Yellow Box in Qingpu:

A Yellow Box in Qingpu: